Wednesday, February 29, 2012

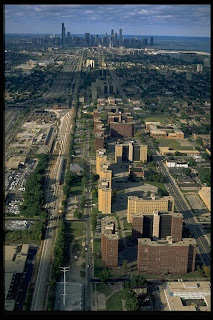

Robert Taylor Homes

Tuesday, February 28, 2012

The Great Chicago Fire

Saturday, February 25, 2012

Sweet Home Chicago

“Sweet Home Chicago” is one of Johnson’s most famous songs, despite the fact that its lyrics make very little sense. Musically and lyrically this song serves as a standard for the Blues genre, but under closer examination of its lyrics, I find a lot of the sentiments we were reading about in “The Southern Diaspara” to be underlying. The chorus repeated through out the song is as follows:

“But I'm cryin hey hey

baby don't you want to go

back to the land of California

to my sweet home Chicago”

The geographic ambiguousness I think is very telling about the commercialized sentiment we were talking about in the great migration: wanting to go home. Home, where things will be better. But in Robert Johnson’s case, Chicago was far from his home (he may have been there once), and instead of longing for the country like the song “Detroit City” we looked at, he’s longing for the city.

In trying to figure out the “land of California” bit, I found one lyrics interpreter who claimed Johnson was referring to a metaphorical California- a place of opportunities and riches. In contrast with “Detroit City” (here’s a refresher http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D6dP1xLk4rQ), where you have a white country musician, lyrically situated in the city, longing for simpler times in the country (pre the great migration, one would assume), Robert Johnson is an African American blues musician, longing for the city, and the opportunities for change it brings. While we had a lot of conversations in class about whether this sentiment for “home” was truly how people were feeling or something that was projected onto society, even within that all-encompassing and elusive “home”, different parts of America were looking for very different things.

Lyrics to "Sweet Home Chicago"

Friday, February 24, 2012

City in the Snow

| Lake Shore Drive, 2011 |

The sheer number of people struggling to move through Chicago today, either locally or as a layover to an international location, is astounding. In 2010, O'Hare was the third busiest airport in the world, hosting over 66 million passengers. The Tollway is expected to generate about $21 million dollars in revenue. (I can't find anything that gives a time frame for that figure, but almost all of that money will be pumped into the city's economy.) Even now, it is easy to see that Chicago is a hub for transportation, both in the U.S. and internationally.

What I find interesting is the fact that railroads are completely absent from the reporting on this transportation holdup. As Cronon illustrates in the chapter "Rails and Water," the railroad system converged on Chicago as the juncture between the East and the West. Clearly, Chicago still operates in this capacity, but the form of transportation has evolved. The question for me remains whether or not flying and driving are more efficient than traveling by train. Cronon addresses the weather dependent road-conditions of the 1830s and 40s, but it seems to me as though not much has changed in that regard.

The Father of Black History

Carter G. Woodson, born in Virginia, graduate of the University of Chicago, is an exact specimen of the diaspora movements described in Gregory’s The Southern Diaspora. It was in Chicago, 1915 that Woodson began the “Association for the Study of Negro Life and History” (1) and later “Negro History Week,” which eventually became African American History Month. (Quick fact: he was a regular columnist for Garvey’s Negro World!)

With his studies and promotion of history, Woodson contributed very much to the idea of a culturally-cohering “black metropolis.” In his book The Mis-Education of the Negro he says that, “The Negro can be made proud of his past only by approaching it scientifically himself and giving his own story to the world. What others have written about the Negro during the last three centuries has been mainly for the purpose of bringing him where he is today and holding him there.” (2) Thus, he talks about the importance of telling your own individual story and on insisting on your own place in history, an idea we've also developed from readings.

Additionally, like The Haymarket Strike with the Haymarket Square Monument, education about history gave blacks a place of unity, a place of pride, and a place of recognition. Woodson said, "Besides building self-esteem among blacks, Negro History Week would help eliminate prejudice among whites." (3) The two go together, as intensive coverage of black celebrities, sports, and music in papers like the Defender showed us.

Plans for a National Historic Site in honor of Woodson are in effect right now and it would be interesting to compare its features to the Haymarket Monument, though it will concentrate on museology rather than symbolic imagery. (4)

Today, African American History Month continues to exist, and although it words its goals with Woodson’s ideas—“truth could not be denied and that reason would prevail over prejudice” when “the entire nation had come to recognize the importance of Black history in the drama of the American story” (5)—there is much criticism of the concept. Morgan Freeman has said, “I don’t want a black history month. Black history is American history.” (6) Interestingly, that was the precise reason Woodson wanted a black history week. How has what was meant to be a celebration of existence become belittling rather than empowering? Certainly, black history deserves more than a month. I think the question is, more precisely, do we still need a yearly reminder that black history does deserve recognition as American History or is the special treatment demeaning and self-undermining in that it labels black history as something separate from regular American History?

Thinking

about this reminded me of our discussions of the varying peoples that have

historically made up Chicago. Whether

it was the influx of people via the railroad that transformed Chicago into the

Metropolis it is today, or German and Irish immigrants, or southern black and

white migrants, Chicago has always been a diverse city formed and influenced by

its people. This idea is thoroughly

expressed in the way the structure physically reflects the city - a city of varying

people, a rich and historical culture, and economic prowess.

Thinking

about this reminded me of our discussions of the varying peoples that have

historically made up Chicago. Whether

it was the influx of people via the railroad that transformed Chicago into the

Metropolis it is today, or German and Irish immigrants, or southern black and

white migrants, Chicago has always been a diverse city formed and influenced by

its people. This idea is thoroughly

expressed in the way the structure physically reflects the city - a city of varying

people, a rich and historical culture, and economic prowess. A Much Shorter Post Than My Last

Reading Trachtenberg on 1893 Chicago World's Fair got me thinking about "Expo 2010 Shanghai China", a revamped world's fair of sorts: http://topics.nytimes.com/top/reference/timestopics/subjects/e/expo_2010_shanghai_china/index.html?scp=4&sq=world's%20fair&st=cse

This Times summary says it outright: the Expo sought "to showcase a polished, vibrant Shanghai that it envisions as a financial capital for the region, even the world." Further, the Expo's motto ("Better Cities, Better Life"), was evocative of Trachtenberg's analysis of the Chicago Fair as "a model and a lesson [...] of what the future might look like [and] how it might be brought about". The similarities don't end there. The face-saving coats of paint and layers of mortar (http://www.nytimes.com/2009/08/15/world/asia/15iht-letter.html?pagewanted=1&ref=expo2010shanghaichina) remind me hastily-applied staff facades of White City; the comparative dysfunction of the city beyond the gates (as evidenced by the removal of the unsightly beggar in the above article, and the growing unrest of the middle class [not to mention the forced eviction of many of the lower class] in this one: http://www.nytimes.com/2007/08/10/world/asia/10train.html?ref=expo2010shanghaichina) remind us that the bright image of a prosperous future presented by these kinds of fairs, now as in 1893, does not apply to marginalized groups. Like the 1983 Fair, the Expo consists mostly of buildings designed to be taken down once the event is over.

Something about the World's Fair concept skeeves me out. Maybe it's that whole fly-by-night glistening facade of perfection thing, or just the fact that urban centers clamor for the money and prominence that accompanies being named, essentially, the seat of progress for all intents and purposes. And then, there's this: http://www.nytimes.com/2010/09/17/us/17bcjames.html?ref=expo2010shanghaichina

"For a World's Fair to work in the 21st Century, it has to be about problem solving." Sure, but the way the 'problems' and 'solutions' are framed by any given host city is invariably a work of "education and propaganda". I feel like the US, given its long history of hosting World's Fairs that pushed imperialist agendas (and a vocal, socially conscious middle class [especially in San Francisco] that would definitely not stand for mass eviction or unnecessary construction and expenditures), would do better to leave this kind of Expo concept buried in the ground.

Workers Strike at Chicago Factory... and it pays off

Three years ago, in December of 2008, factory workers at Chicago's Republic Windows and Doors factory were informed that Bank of America was cutting off its funding, and the factory would be shutting down. The workers were given only three-days notice and were not payed severance. Unwilling to take this lying down, 200-250 of these workers organized a sit-in at the factory, refusing to leave until they were given what was owed to them. Note: this was in winter... in Chicago.

What I find most interesting about this story is that even three- years after the fact, it is not clear whether or not the factory or Bank of America is to blame - neither was willing to claim responsibility. This reminds me of the discussion we had after reading Martyrs and Monuments, and the problems many workers faced once there was no longer a single owner to be held accountable for a company's problems; but rather a CEO, shareholders, etc. In this case, according to the factory, Bank of America abruptly cut-off all funding to Republic and despite the factory's request for severance for their employees, this request was denied. However, the Bank tells a different story. This is a statement pulled from NY Daily News:

"Although we are a lender with no obligation to pay Republic's employees or make additional loans to Republic, we agreed to extend an additional loan to be used exclusively to pay its employees," David Rudis, the bank's Illinois president, said in a statement.

(full article: http://www.nydailynews.com/news/money/republic-windows-doors-sit-in-ends-workers-celebrating-article-1.357063)

In the end, the Bank and Republic Window and Doors reached an agreement and the workers were given 8- weeks salary and two months of healthcare. The strike lasted 6 days, and unlike the Haymarket Riot, it remained peaceful.

"What government gives, government can take away"

From the Delta to Chicago

The circle of music doesn't have any boundaries. While I was looking for examples of The Butterfield Blues Band performing "Walkin Blues", I came across Robert Johnson. Also a Delta blues man like Muddy Waters, Johnson recorded his cover of the blues standard "Walking Blues" in 1936. The tie in to this is the "A" side for the single: "Sweet Home Chicago".http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dkftesK2dck&ytsession=A5eC93yfGx3p This song has become one of the anthems for the city of Chicago. The lyrics have ben altered to reflect a more Chicago centric tone. The original references to California are now gone in the modern renditions.

Back to my original thought about how familiar "Country Blues" sounded; listening to Robert Johnson's performance of "Walkin Blues"http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MEsQikthT3Q&noredirect=1 from 1936 brought to light why Muddy Waters' song resonated with me. Muddy Waters' tune from 1941 was from the same time period and took cues from the blues standard. The circle of music is nicely intertwined with Chicago on many levels: Muddy Waters bringing it up to Chicago and electrifying the delta Blues, Paul Butterfield embracing the blues from his home town covering a Robert Johnson song (Walkin' Blues), and Robert Johnson's "Sweet Home Chicago" becoming a song embraced by the city.

All Jokes Aside

Let the Subjects Speak for Themselves

I came across this website, called DuSable to Obama: Chicago’s Black Metropolis, which is very applicable to today's material and discussion, not to mention a lot of fun to browse through:

http://www.wttw.com/main.taf?p=76,3

The website depicts the evolution of the African-American community in Chicago from its first black founder Jean Baptiste DuSable (If you check out this page on the site with information of DuSable, http://www.wttw.com/main.taf?p=76,4,3,2, you can watch a video of Leorne Bennett, who says that that “the biggest secret in the history of Chicago is that Chicago was founded by a black man”) Leorne is one of several African-American figures on the webpage who gives first-hand accounts of the community in Chicago. Thus, similar to the conclusions made after reading Miles and Wu, the site keenly acknowledges that the voices and of individual stories are crucial in understanding the intricacies of history.

Robert Sengstacke, a Chicago Defender photographer, also stresses the importance of capturing individuals “as they are” in his photojournalist work. Check out his video clip on the bottom of the home page to get an idea of how he captured and promoted the African-American community as “joyful” and “peaceful yet strong” in contrast to the sort of “anthropological examinations” or white depictions that focused more on weakness.

Here’s a link to Sengstacke’s website that gives access to his photo galleries: http://www.sengstackeimages.com/Welcome.html

On this site, Steenberg writes, “Some people write history with a pen. Bobby writes it with a camera” and notes the photographer’s mission “to confront America with its self deceptions about his people”. In this way, Sengstacke truly utilizes James Gregory’s notion that journalism and photography are not merely artifacts but factors in history.

Thursday, February 23, 2012

The Response to "Birth of a Nation"

I also found an opinion piece entitled "Birth of a Nation: The Most Preposterous Adversary of the Negro Race of the Twentieth Century" in the Chicago Defender from October 2, 1915 that clearly defines why the film is so deeply troubling:

“The entire picture is one for the purpose of creating race prejudice and in it is seen a complete exaggeration of history… There was actually no such thing as a black domination in the South. This picture is shown simply to create prejudice and stir up stride and it is beyond my reason to find how the great men and women of my race and of this great metropolis can rest contented and submit to such an indignity.” –Evans Ford (The Chicago Defender Article)

Obviously, I knew that the film is considered controversial today, but I was unaware of the scope that the backlash against Birth of a Nation had at the time of its release. Taking all of this into consideration, I also had not heard about Oscar Micheaux, and I was really intrigued by him because he chose to challenge Griffith. Within Our Gates (1920) was a direct response to the crude, prejudiced stereotypes found in Birth of a Nation. He truly was able to use the rise of the motion picture industry to his advantage. The rise of his films injected the black perspective into American consciousness, and cinema served as an advanced way to communicate the stories to the public that were not being told. Rather than using it as a way to spread hateful messages, I feel that Micheaux’s legacy was such an important step in utilizing a huge strength that the medium of film possesses: making issues seen in the public eye.

Ashes to Ashes, Farms to Farms...

Immigration in Chicago Today

While our unit on Chicago thus far has focused on historical periods of immigration to Chicago, beginning in the nineteenth century and ending with the second phase of the Southern Diaspora that culminated in the 1970’s, we haven’t touched on the issue of immigration today. Cronin focused on the influx of immigrants in the nineteenth century who flocked to the prosperous, expanding city, but people continue to immigrate to Chicago today in the 21st century.

A New York Times article published on February 9, 2012 entitled “Suburban Chicago Schools Lag Behind as Bilingual Needs Grow” focuses on the Latino immigrant population of Chicago. The state of Illinois mandates public schools to provide bilingual programs, but a recent report reveals that many schools have failed to adequately provide for their bilingual students. Many of the students learning English (roughly 80% speak Spanish as their native language) struggle academically.

Since 2005, 25% of suburban school districts doubled their number of English-learning students. Plainfield School District tripled its size of English-learning students. In examining the entire state of Chicago, the number of English-learning speakers increased 10% from 2009 to 2011, resulting in a total population of 182,600. White eighth graders scored 17 to 23 percentage points higher than Latino eighth graders on the same reading achievement test. School districts have struggled to find bilingual teachers to helm its dual-language program where students are taught in both their native language and English to ensure they learn fundamental concepts before beginning to improve their English skills.

In an American society where literacy is fundamental, many of these immigrant students are struggling to learn basic subjects in school because of the language barrier. The Latino struggle echoes the many black southern migrants a century before who came to Chicago unable to read or write. We touched on upward mobility in our last unit, and the idea of immigrants coming to America for a better life, evidenced in one of the blog posts on students crossing the border from Mexico for an American education. But how will these Chicago students succeed if the public schools are failing to teach them the English needed to rise up and make something of themselves?

Essence, Representation, and Hip Hop - Chicago!

clips!

About my people she was teachin me She was really the realest, before she got into show-biz

_from_east'.jpg)